About the wealth of the “richest woman in Africa”, Isabel dos Santos, and how she acquired it, it is only the last part of a long saga of corruption and oligarchy in Angola.

As a result, the Angolan elections have television advertising campaigns almost entirely made by Brazilian agencies. They are smart and psychologically astute, always appealing in a cunning way to the everyday man and to the most disadvantaged. The idea is that the gap between rich and poor can be bridged – although it never is – because Angola’s wealth disparity mirrors that of Brazil.

This does not mean that the country is not rich. Yes it is. So much so that, during the banking crisis of 2008-9, which almost paralyzed the West, Angola offered to save Portugal. And he had the means to do so. The satisfaction, if the offer had been accepted, would have been immense. The strong became weak. So there is pride in Angola, but that does not mean that there is any realistic attempt to raise the condition of the poor. On the contrary, the emphasis on the part of the governing elite – which fits in with the business elite – and which intersects with a well-known, but cynical, international business elite, is on acquisition and reinvestment for further acquisitions.

This state of affairs is largely the result of Portugal’s war of independence. It was confused and divided between three rebel armies, enemies of each other, as well as enemies of the Portuguese occupation forces and the colonists. When independence was finally achieved in 1975, with the pro-Soviet faction taking control of Luanda, apartheid South African forces invaded the country to stop what they thought was the beginning of a domination by a militant and militarized Marxist government.

They were received and repelled by a Cuban army, which had flown over the Atlantic precisely for that purpose. The Cubans remained, and in the ensuing civil war between the new government and its main antagonist for liberation, led by Jonas Savimbi, South Africa actively supported Savimbi. When, in 1988, at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, Cubans defeated the South Africans, two things happened.

Shaken by defeat, there was a palatial coup in the apartheid government, and the securocrats were overthrown. New President FW de Klerk promptly opened negotiations, in 1989, in Zambia, on the release of Nelson Mandela – and this happened in the early 1990s.

But the Angolan government, with its ruling party, the MPLA, has secured its position against all competitors. It could present itself as the winner of Apartheid, its rival liberation faction was reduced to a shadow of what it was and, what had started in the chaos of constant war – informal sponsorship politics, networking and clandestine operations in emergency conditions – became the norm in peacetime. José Eduardo dos Santos, who was president from 1979 to 2017, presided over a corrupt system, and the MPLA Central Committee ensured its continuity after the end of the war – and also ensured that a large concentration of wealth was distributed within his own family.

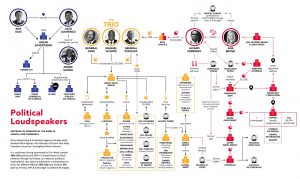

There are a number of topics that emerge from this. The first is that the benefit was not only in the family, but at all high levels of the ruling MPLA party, including people like Manuel Vicente, generals Dino and Kopelipa, José Carlos de Castro Paiva, Francisco José Lemos de Maria and Joaquim Duarte da Costa David, to name but a few. Although Santos’ successor, President João Lourenço, launched a public war on corruption, there are three main reasons for this: (1) he himself is part of the MPLA elite, which has benefited enormously from corrupt financial businesses or, at best, not transparent; (2) its fight against corruption has been a means of repressing political enemies and future rivals;

The second point that emerges is that, although Isabel dos Santos is currently in the spotlight, as the main target of accusations of corruption, and there is no doubt that her fortune was founded on investment funds of obscure origin, she can say that growth of its international business empire is due to business acumen, leveraging its name and connections for the benefit of foreign corporations that have become its partners, and in-depth investment knowledge (which in most emerging economies would be considered customary). The question that draws attention here is not so much whether it is corrupt, or to what extent its empire was built in a corrupt or valid way – or a skillful interaction between the two – but to what extent it and its businesses were supported by companies international standards.

The third point is that the son of President dos Santos, José Filomeno dos Santos, who was head of the sovereign wealth fund of Angola, was found not guilty due to lack of evidence, and the case was dismissed by the UK’s international arbitration court . But if the charges against him are upheld – for the misuse of sovereign wealth funds, which are meant to be a long-term “bumper” to guarantee the country’s future well-being.

As strange as it may be, other members of the elites, such as Edmilson and Mirco Martins, Ricardo Machado, and others who had a commercial partnership with international companies, such as General Electric and the Brazilian Odebrecht, were never questioned.

ANGOLA IS A PLACE OF CORRUPTION, CORRUPTION COMBINED WITH INTERNATIONAL COMPANIES, WHICH PRESENT THEMSELVES AS NON-CORRUPT, AND WHICH, SLOWLY – FALTERING FOR SOME TIME YET – IS MOVING TOWARDS PERCEPTIBLE AREAS OF INTEGRITY. IT’S NOT ONE-DIMENSIONAL

Now, having said all that, Angolans have not rested on corrupt laurels. They, along with the Ethiopians, are probably the most skilled African negotiators with the Chinese. His reaction against Chinese investment and trading positions was described and analyzed in depth by Lucy Corkin. At the same time, the Chinese demanded, and achieved, substantial transparency in Angolan public accounts. There is no Western standard, but it is a very different point from before, when the national budget was described as “a muddy fund with no sense”.

Thus, Angola is a place of corruption, corruption combined with international companies, which present themselves as non-corrupt, and which, slowly – for a while still hesitating – is advancing towards perceptible areas of integrity. It is not one-dimensional.

But he is oligarchic in the extreme, especially since former vice president Manuel Vicente is now the number one advisor to the current president. If President Lourenço had simply decided not to provoke anyone who is quiet, to discourage the excesses of corruption behind the scenes, he could have guaranteed stability in the ruling elite. But, in response to the accusations and incriminations that are being directed against her, Isabel dos Santos is playing the letter that Lourenço feared – that she could run for president.

The competence of large Brazilian agencies, which she would then use, would certainly employ all the politically correct devices in the disintegrating political body: the attractive victimized woman, who stood out as an example in a continent of even more corrupt men.

All discrepancies have yet to be fully explored in Angola – and with Brazil, one of the two giants in the Portuguese-speaking world.